Sable

“Cozy” has been the new “addictive” as of late in video game review writing. I tend to notice when certain words start trending across websites. And ever since Spiritfarer called itself “the cozy management game about dying,” cozy has indeed latched itself onto many a review writers’ lexicon.

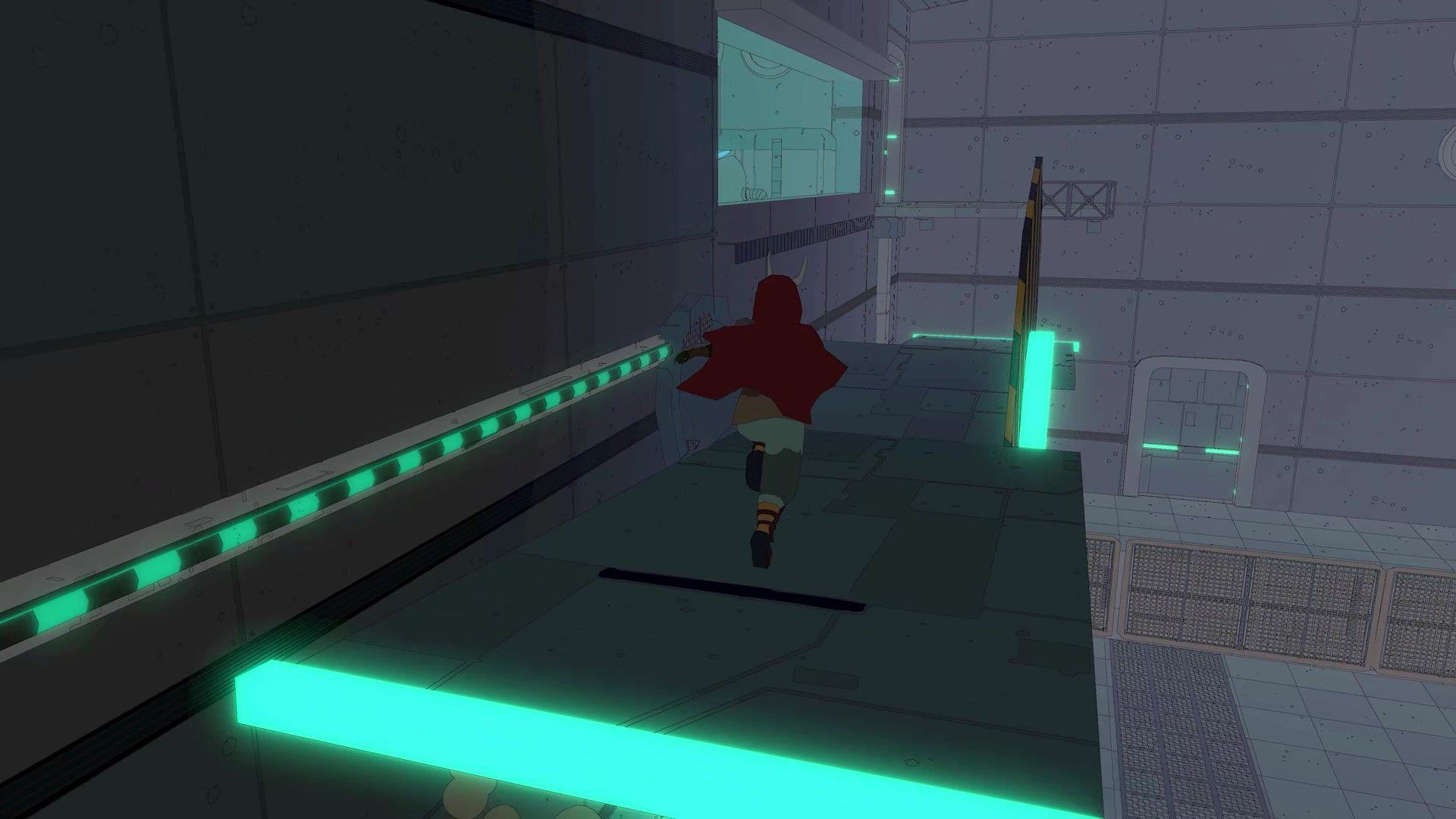

So, I figure it’s my turn. Sable is a cozy puzzle-platformer game about getting out. Sable gives you masks to swap out so you can search for your own identity. It gives you the keys to your first sand bike, just like you’re experiencing the freedom of the road for the first time. It has an it-takes-a-village level of tenderness written into this coming-of-age story. Even if you aren’t a Spiritfarer pressing X to hug sad-eyed creatures floating along in the afterlife, you’ll wish you were.

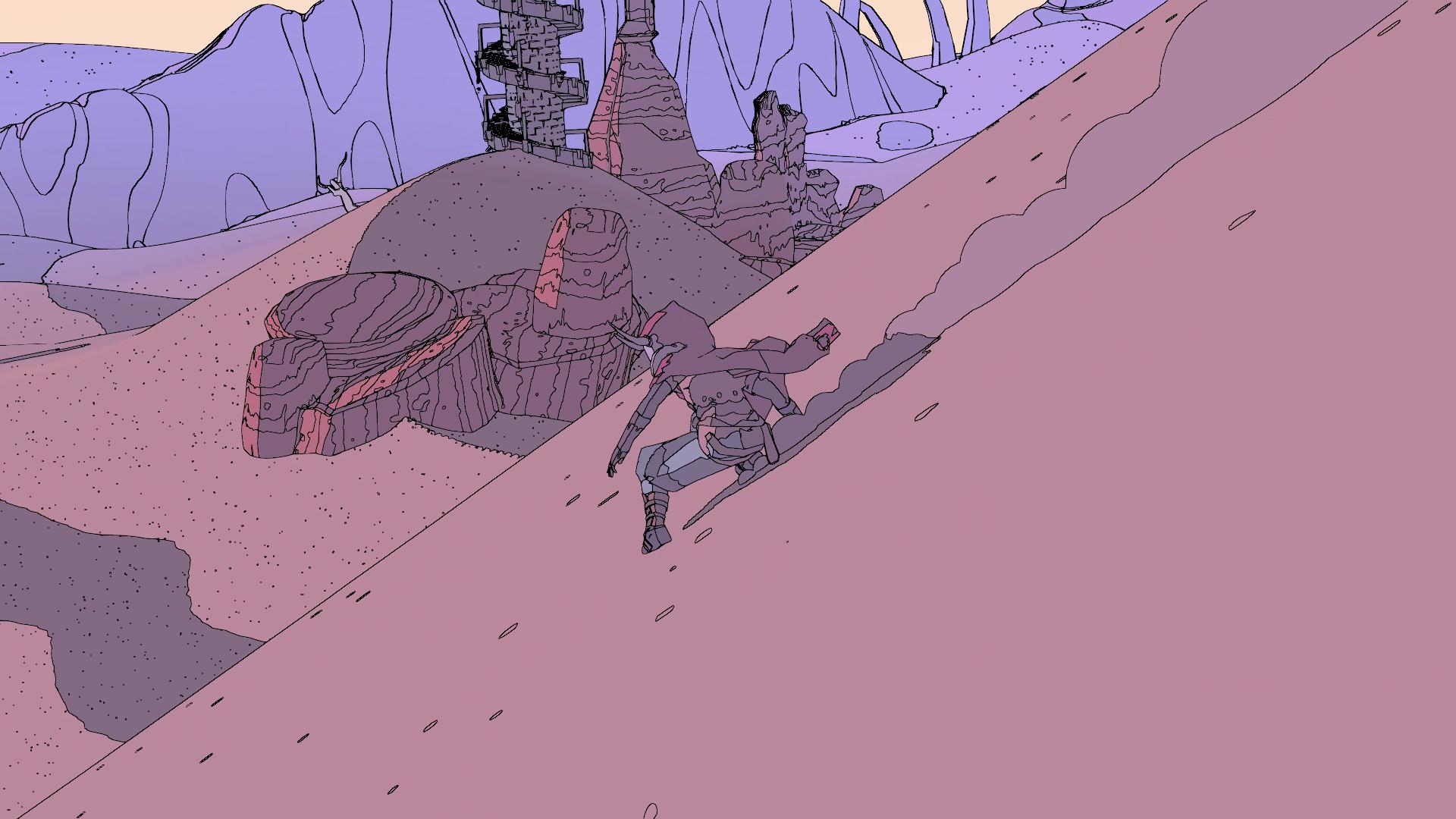

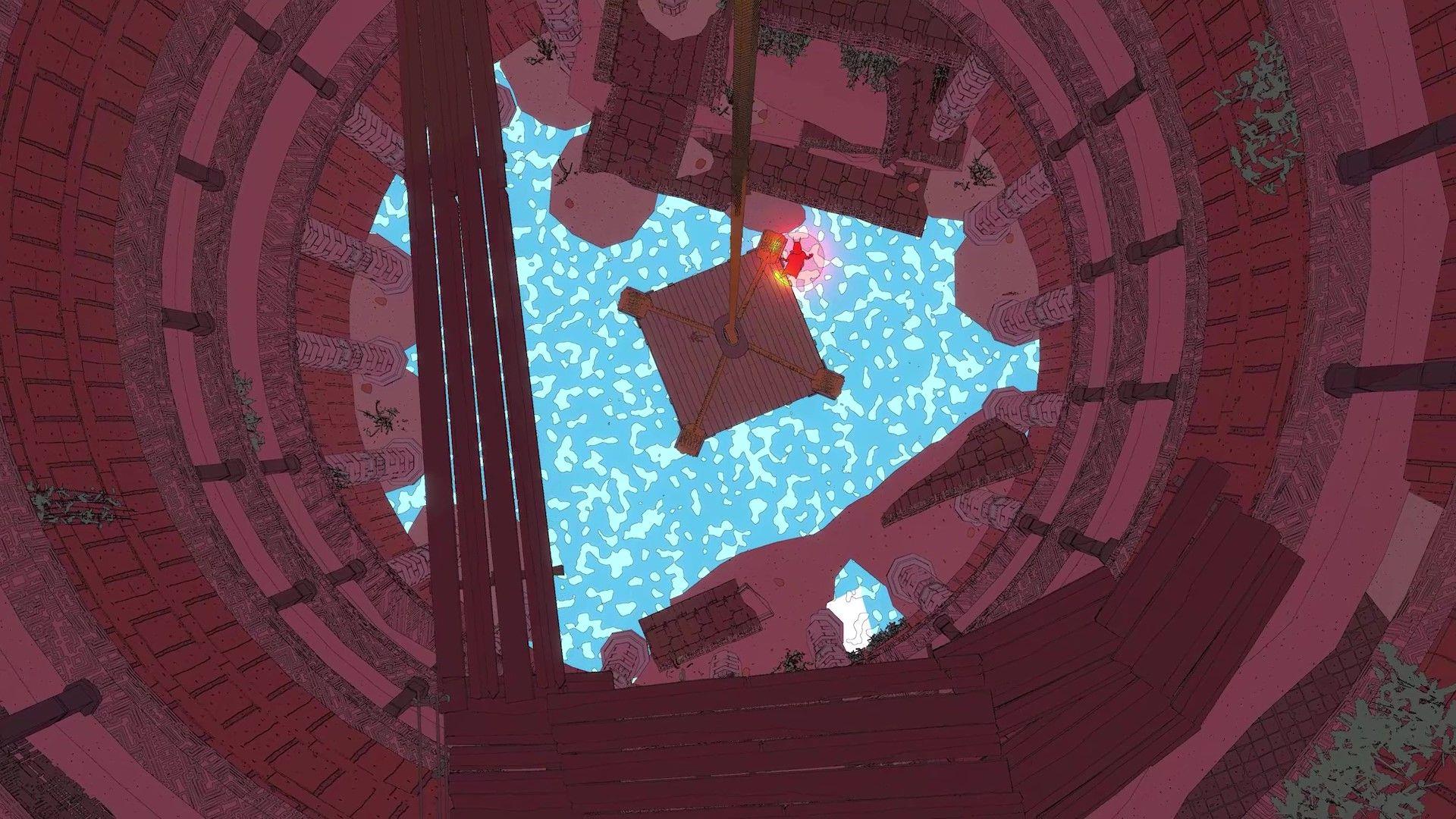

The word “sable” is the color black. Which is an ironic name for this game. Because black draws up the simple and simply beautiful lines of the game world, but you’ll never find a swatch of flat black painted in the shadows, or in the depths of a crash-landed spacecraft, or even beneath the gray husk of a dead sand worm.

Here’s the second piece of art major nerdery I can bring to the table: The color of a thing is not that thing’s color. If you see a red ball, that ball is absorbing every color of the spectrum except red. The red is reflecting off the ball, which is why your eye receptors pick up the color red when you look at that ball. That ball is absorbing every color of the visible spectrum. Except red.

This is why the game Sable, which means “black,” is anything but black. It is not dark. It doesn't have a hurtful bone in its body. Sable is kindhearted and open and willing and in conversation with you and uses your chosen pronouns and really it just wants to hug you right back.

The main character is also named Sable. And, in a like manner, she is absorbing everything around her—except for what you see of her. What you see of her is merely her reflection, or what she projects to others. I traveled to far-off lands and spoke with off-kilter people. Some of those people gave me components to acquire different masks. And since you're never without a mask, I took those components to a wordless seer that had me physically reach deep down inside of them to pull out my next mask, my next projection of who I am.

I switched out my masks more times than was necessary. And it’s never necessary. It would be callous to say that the masks Sable wears mean nothing. But nobody comments on them. No additional dialogue trees branch out if, say, I’m wearing my cartographer’s mask or my child’s mask. I don’t get a better armor rating the moment I discard my tribe’s Ibexii mask for the machinist’s mask. It’s only a reflection of who Sable is, when every single one of her other masks, shirts, and pants further speak to who she is inside. The red ball isn’t red, it’s everything but red.

Sable’s gameplay isn’t quite so mind bending. She is of age to finally go out on her “gliding,” the time in everyone’s life when they head out on their own to learn about the world at large. It’s an important time of reaching out beyond arm’s length and seeing what grabs you. I’m cutting a dusty rooster tail across a Journey-like landscape in order to learn that gliding is all the friends I've made along the way.

I’m not even mad when I say stuff like that. Sable has awakened a sense of discovery and exploration that is rare for me, despite the fact that I’m urgently, desperately looking for it in every video game I play. I haven’t had this much fun climbing—with exhaustion ticking away at me—since the earliest days of Assassin’s Creed.

I also haven't had this much fun cruising in my sand bike across dried-up ocean floors and juking between sandstone archipelagoes since Mad Max. There’s nothing better than doing it in my customizable ride, too, which I change the components out of every chance I get. It started off as a Star Wars-looking lithium battery with low wings. Now it’s an Autobot alligator with sand flea legs and a roadrunner tail. Faster and more maneuverable than that old jalopy, too. Like my masks, like my clothing, my ride is only one reflection of everything I’ve become along the way.

So I pull out the map. I scan the legend-less topography. I drop a point or two into the GPS and I take off with reckless abandon. Sometimes that map drops a hint that there’s something special here. Sometimes I see an alien shape crest over a tall dune. Sometimes helpful people along the way (everyone is so helpful) point me in the right direction. Sometimes some very good (meta) gaming advice also comes out of the mouths of these people:

“My advice? Try to have fun. There’s a lot to be said about ritual and independence and all of that out there, but...the world’s an easier place if you put joy first.” Thank you, Hilal. Aside from knowing where the gas and brake are, that’s all the tutorial I needed.

The tribe Sable is from live among ruined ship parts. Spaceships. The first settlement I reached after leaving my tribe was a bunch of machinists and scrappers. They’ve built their homes atop ridges that look like battleships rising from a dusty ocean. The machinists’ shop looks like tugboats riding low in the water. But the scrapper’s life hints at the mystery you unfold in the desert. The mystery of who came before, where these massive spaceship corpses came from, and is perhaps any of them my mommy?

Despite being given a minimalist clock that you’ll mistake as currency for a while, the day night cycle is crucial to the setting’s mood but nothing else. The stars feel like bright splatters from a Jackson Pollock painting. I go from the Wile E. Coyote countryside of my O.G. tribe and into a sandscape of Easter Egg purples and dusky pinks, followed by the twists and turns of bigger settlements as flash mobs of citizens protest being powerless. (I’ll pretend that isn’t a direct reference to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical In the Heights.)

Sable is a rare thing: A post-technological society filled with the hope of a return to nature, and perhaps even a return to the stars. With people that speak kindly. Even those engaged in class wars maybe seem quirky more than they are evil. They hold each other sincerely and cry honestly. It’s like that Wholesome subreddit turned into a video game.

It’s an excellent setup, considering linearity vs. sandbox gameplay, to have your main story mission simply be “Get out there and explore stuff, kid.” It makes every instance of getting sidetracked leisurely. It makes every side quest of central importance. It makes the journey the destination. Sable is a pleasure. Yes, I realize how corny that must sound.

Many times I plotted no course. I’d simply pick a point on the compass and just go. Sometimes it was worth biking beyond the known parts of my map just to see what colors the land and sky would change into. To see where Here There Be Dragons is, and to find those dragons turned into a graveyard of sun-bleached bones and little beetles burrowing in their ashes.

The soundtrack, so sincere on the main menu, is sadly my least favorite thing of Sable’s entire experience. There’s no need for me to be mean about it. But I would’ve preferred something less overproduced, more lo-fi, and simultaneously more and less whimsical. The rest of the soundtrack, when out on your gliding, is sparse enough to be nonexistent at times (which is nice) and humble enough to step out of the way of the visuals and the metaphors (which is also nice).

I take it back. The soundtrack isn't the thing I like the least. It's the glitchy menus. I was super nervous one time when I had to quit playing for the night, and the menu screens were glitching on Save Game. Couldn't save. I still had to hard shutdown and hope for the best. But when I’d fired up the game the next day, it’d autosaved where I was. Luck won out.

Item descriptions also get themselves confused when you buy and sell things from a merchant. Or the different color customizations for your bike get all misaligned and can't be selected. Sometimes my bank account balance gets stuck onscreen—which is only noticeable because the HUD is otherwise wonderfully and completely empty except when and where it's needed. There’s nothing that doesn’t get cleared up by saving and returning to the main menu and loading back in. But some things clearly aren’t running as intended. Eventually I found out that 75 percent of my menu problems stemmed from using a PlayStation controller on my PC. I had fewer glitches when I’d switch to using a mouse. Playing a hybridized version of both mouse-and-keyboard and gamepad isn't ideal, and it doesn't clear up every problem, but it at least keeps the game playable.

Sable is probably my open world game of the year. One that haunts me when I’m not playing it. One that taunts me to recall my own “gliding” years in life. One that wants me to soak it all in and carefully select the parts I want reflected in my gameplay experience. It's a nice change of pace heading out into a wasteland, sifting through scrapyards, and interacting with different tribes of people, and finding hope floating on top of it all.

Rating: 9 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile