Loop Hero

This wasn’t how it was supposed to go. Loop Hero wasn’t supposed to introduce me (really introduce me) to roguelikes. It wasn’t supposed to make me a believer in deck building. I wasn’t supposed to fall in love with tile placement. But Loop Hero has done all of those things.

It’s even made me appreciate its terrible name. Because while it was being workshopped, when the whiteboard was out and everybody was throwing names at the wall to see what stuck, it was probably given names like: Ring of Remembrance: Road of Resistance, or The Round Shape Respawning in the Dark, or Dang It Somebody Already Took Path of Exile But That Would’ve Worked. Then, offline and in casual conversation, while the developers came up with a dozen fantastical names for the protagonist, they somehow kept referring to him as their little “loop hero.” Until one day somebody made the command decision to stick with it. That’s a bold move, Cotton, as they say.

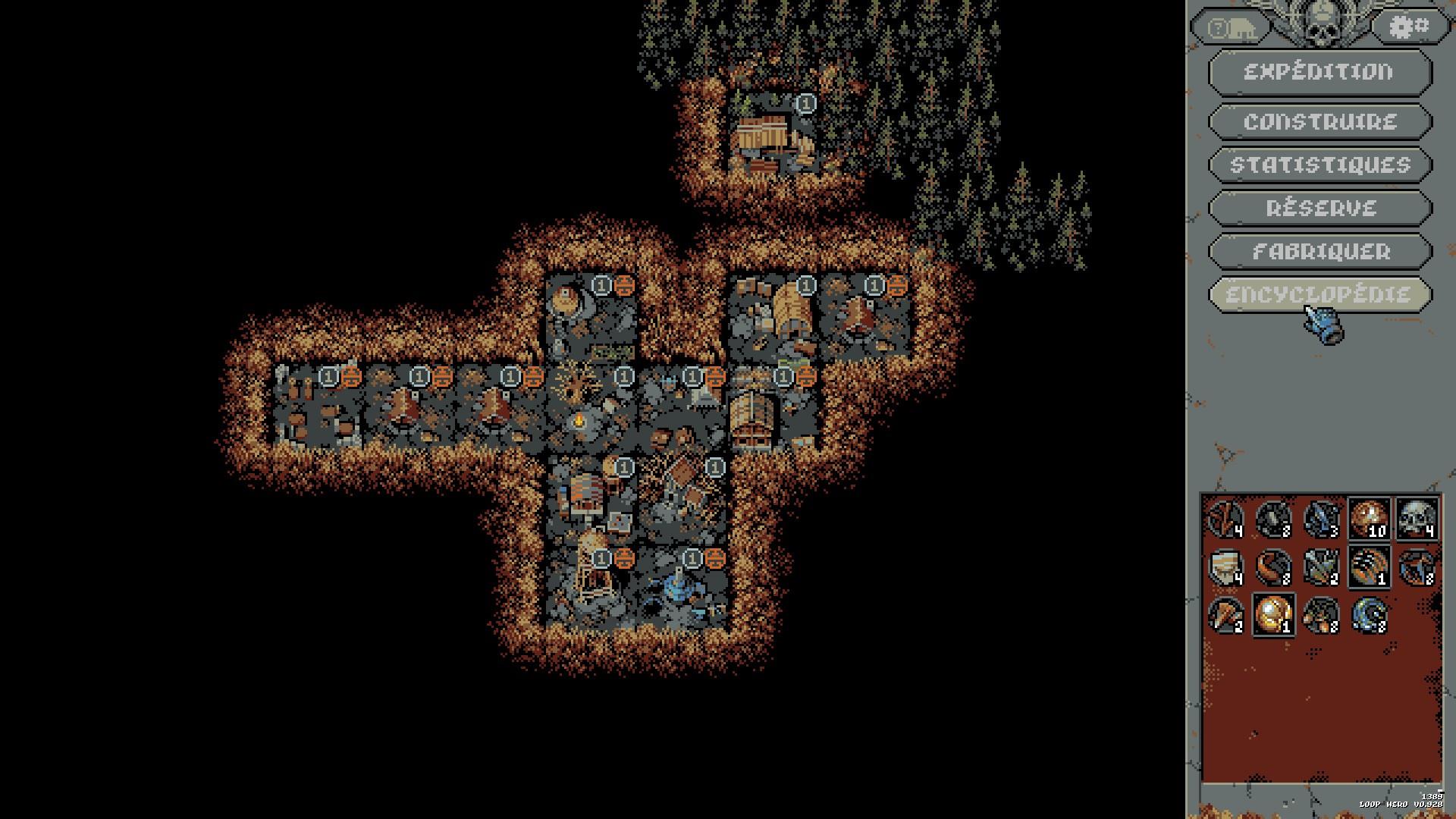

This is the loop. This is the hero.

The loop changes shape between runs, but it always does two things: One, it begins and ends at your camp, and two, it takes about three in-game days to run the loop. If you’re having an incredible run, it’ll take up the entirety of your lunch hour. If you’re having to retreat, you fit in a couple runs. Rising up out of the swirling but utterly still darkness, the loop is the stony path that always brings you home, yet the loop is something you’re rebuilding from nothing.

Think of The NeverEnding Story. At the end of the movie [spoiler alert], the Nothing has destroyed everything—except for a single surviving grain of sand, and Bastion must rebuild all of Fantasia from that grain of sand. Your loop hero has a similar task. There is nothing left of the lands you remember, and you must rebuild it by, basically, killing slimes and placing the cards they drop onto the game board.

At the beginning of each run, I build up a campfire story in my mind. “All I could remember at first was the path, young’un. But then a mountain rose in the distance, a flowery field at its feet. I wasn’t two days out from camp when I rounded a bend into a forest grove where hungry rat men lie in ambush to make me their stew. I killed them and remembered the old world, then placed an inland lighthouse that would speed my way in those dark times.” My NeverEnding Story begins again.

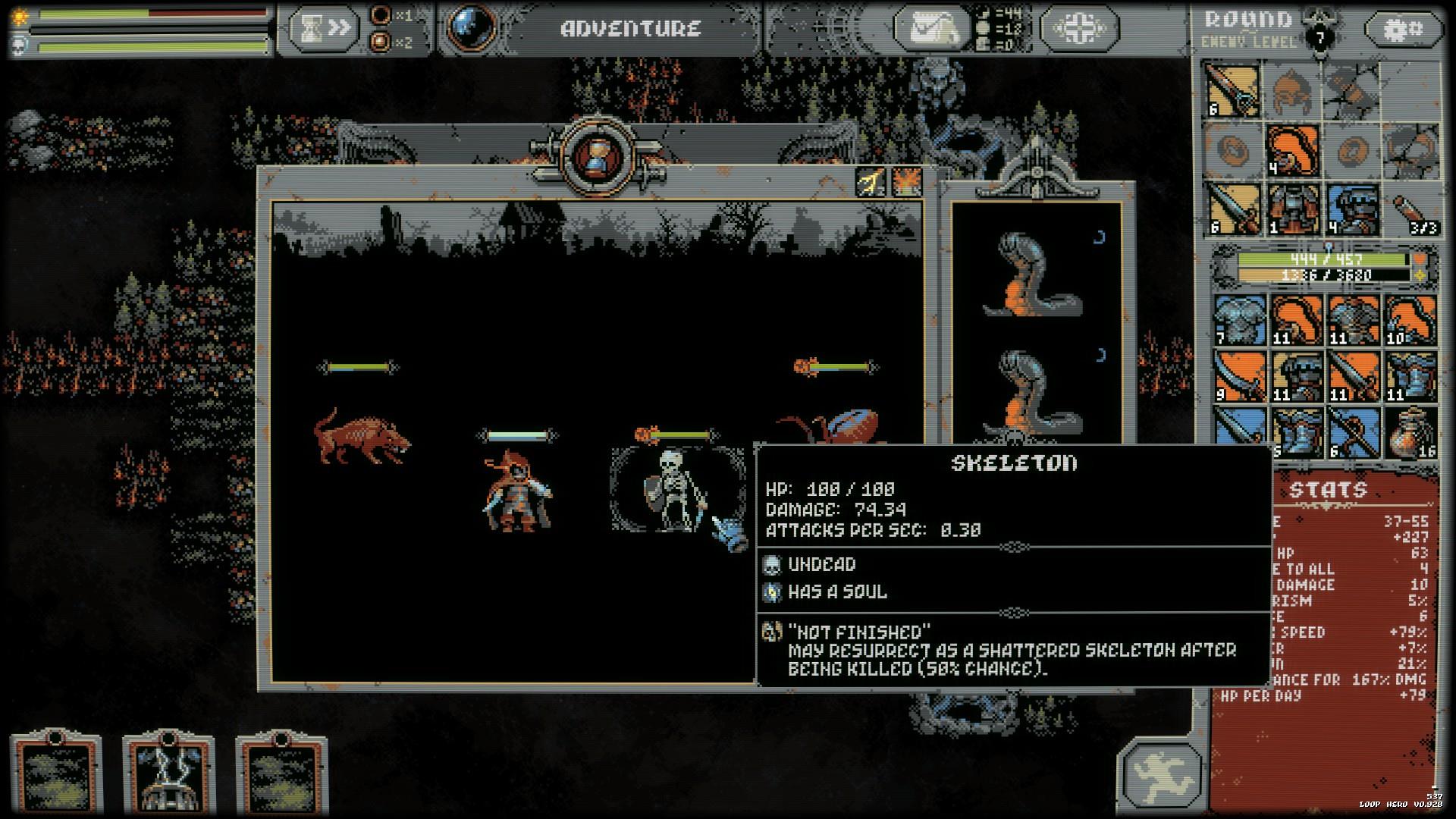

You place a cemetery on the path and every few days a skeleton emerges from the cemetery to fight you. You place a vampire’s mansion adjacent to the path and vampires emerge from their coffins to fight you. You place rocks next to a meadow outside of the path and, thankfully, they add to your strength by building up your hit points. You place a three-by-three square of rocks together and it makes a mountain out of a molehill, but now harpies swoop down from their frozen nests to fight you.

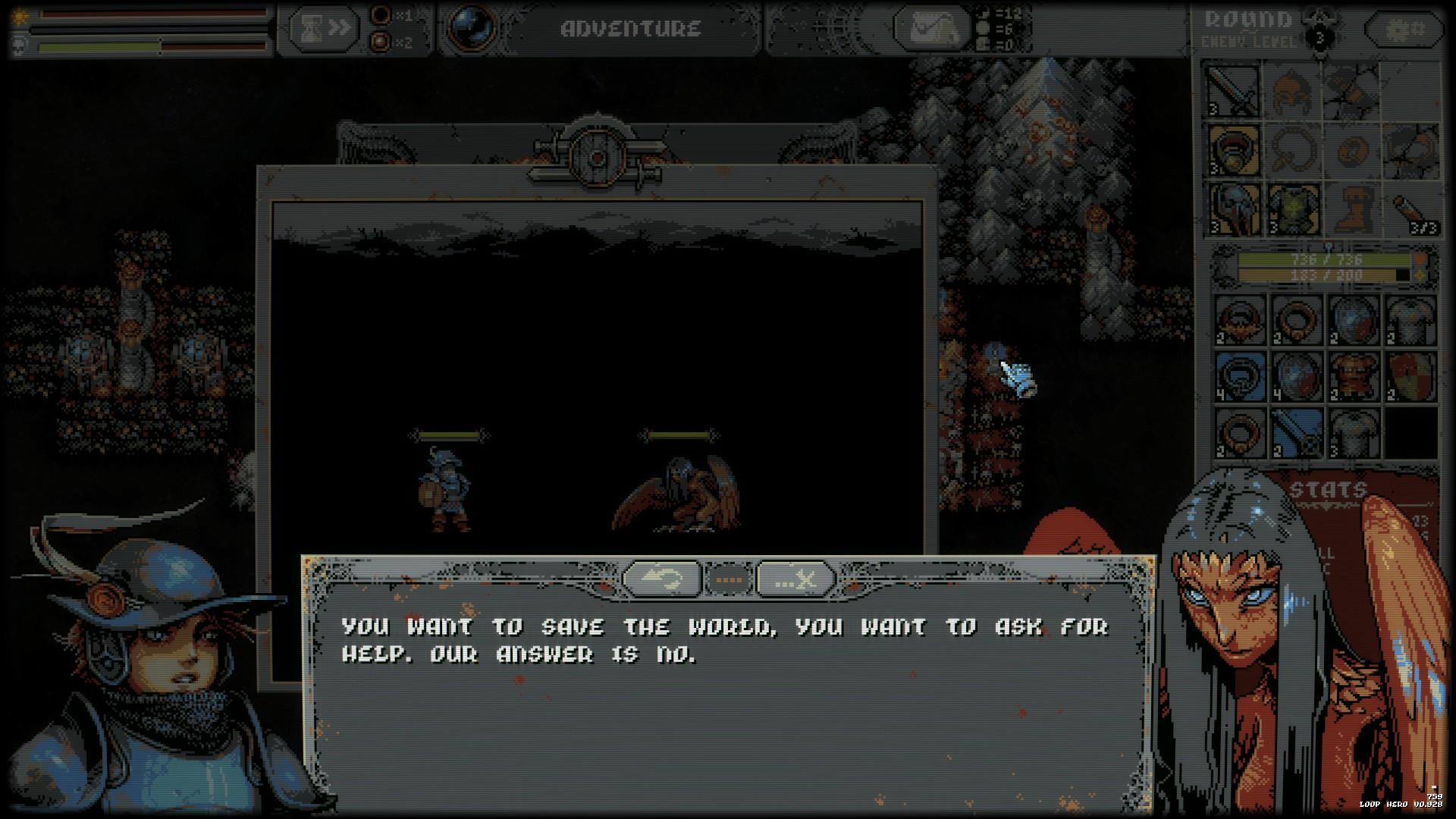

Everything wants to kill you in Loop Hero. Even the vampires that try to warn you away from their hunger and hate. Even the harpies that don’t believe in you or your quest. Even the bosses that know you’ll fight them again and again before all is said and done. Even the things that help you have associated costs. The mountains that add hit points also add goblins to the loop. The towns that heal also assign you side quests to fight tougher monsters. But wait until you see what happens when you place a vampire mansion next to a town. Let’s just say that there are a lot of interactive cross-play between tiles you place. Sometimes that cross-play makes things better. And sometimes it makes things worse before they get better.

What’s eye opening about Loop Hero’s quest is that you’re not entirely sure why you’re doing this. At least not at first. You want to restore the world. You want to rebuild what was forgotten. You want to bring back memories, no matter how faulty, back into remembrance. But that paradoxically means you can’t just bring back only good things. You have to bring back the bad with the good. You’re in no position to build a utopia out of nothing. You have to build with the pieces that are given to you, and most of these pieces want you dead.

The path is dark and fraught with dangers. But it also has loot. The loot will get your hero through this. The arms and armor. The necklaces and boots. The rings and grimoires. As your enemies level up with every loop, the loot they drop levels up, too. The basic math-loving part of my brain triggers with each drop. Stick with my axe that does high damage, or swap it with a sword that does less damage but has a faster attack speed? Do I wear the rings that let me summon extra skeletons, or switch them out with rings that boost my vampirism and evasion?

Loop Hero builds slowly. Too slowly at first. I felt ready for the next layer of complexity before the game was ready to give it to me. I was being naive, of course. Loop Hero is wonderfully paced. I needed the extra time in the beginning to learn through failure. I died a dozen loot-decimating deaths before I accepted the “failure” of a strategic retreat. I prematurely summoned the first boss before I realized I controlled when that boss was summoned. I painstakingly mouse-hovered over every piece of equipment once I figured out that level alone was not the full measure of a weapon’s use.

The loop is, of course, where the brunt of the, uh, gameplay loop takes place. You fight slimes at first, the jelly-like lifeblood of the land. You pace yourself as you drop more and more enemies on the loop. They drop more and better loot (the game must’ve been so close to being called “Loot Hero”). And you also bring home resources from these fights and tile placements. You always come back to camp, home base. There, you decide if you’re going to go around the loop again—the enemies leveling up, the loot leveling up—or if you’re going to retreat back to camp. “Retreat” on the camp tile, you take 100 percent of your collected resources home with you. Retreat somewhere out in the loop, you keep 60 percent of resources. But if you die out there in the loop, where some auto-battler fight ended up being the death of you, then you get dragged back to camp, unconscious, with only 30 percent of the sticks and stones and fragments of memory you picked up.

There’s no permanent death in Loop Hero, which precludes it from being a by-the-book definition of a roguelike. But there are procedurally generated levels, even if you’re the one generating them. There is turn-based gameplay, even if you have the ability to let it run seamlessly from fight to fight. And there is grid-based movement, even if a lot can happen from the time you enter a square until the time you leave it.

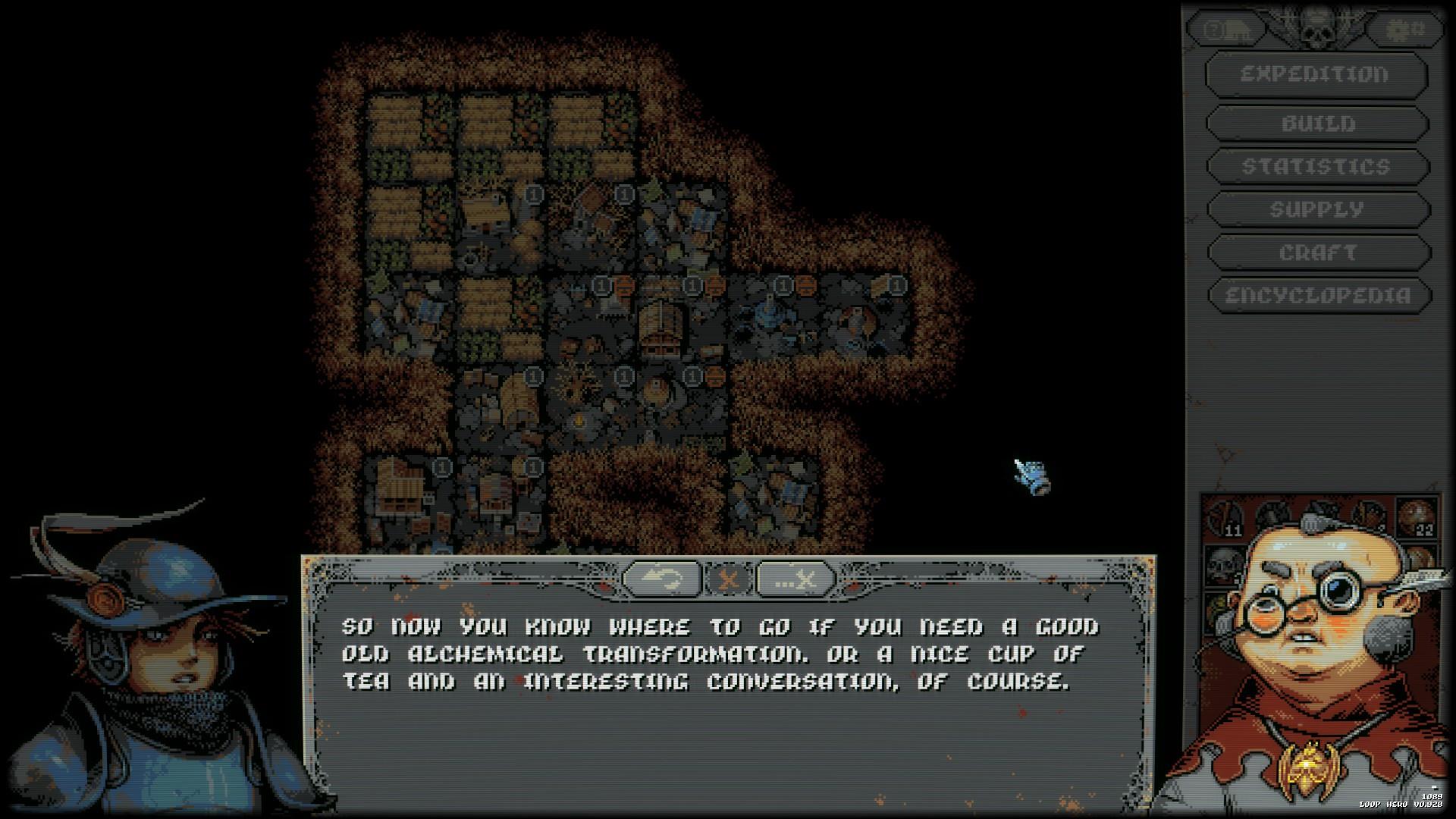

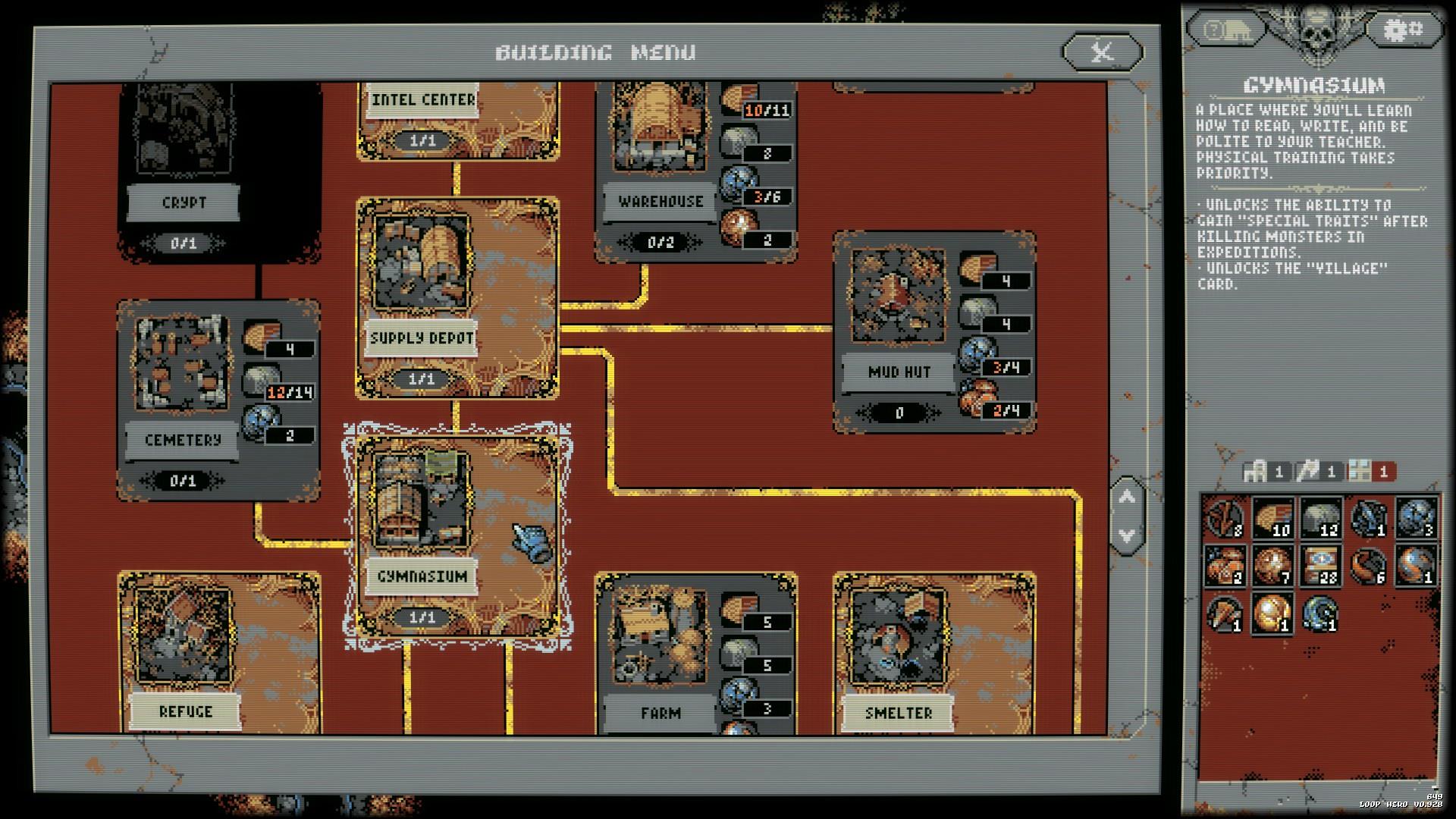

Back at camp is where Loop Hero does some base building. It’s no SimCity. It’s top-down in perspective and, somehow, even more unsightly than the graphics on the loop screen. Percent by excruciating percent you build up passive benefits to your hero. A cafeteria gets you some more hit points. A mud hut lets you find and craft furniture for happier residents. A farmhouse plops multiple fruit and veggie fields, pushing out the boundaries of your new hometown.

Loop Hero isn’t that pretty. I’m not going to lie. I could post screenshots all day, and none of those screenshots would convey how excellent it feels to go around that loop again. Sure, each individual sprite looks okay. There’s a pixelated mountain. That’s a pixelated bandit. I (certainly) appreciate the grime that coats everything. And there’s (absolutely) artistry in Loop Hero’s visual limitations. The up-close character art is stunning. But again, screenshots of the loop itself didn’t talk me into trying Loop Hero. Screenshots didn’t convince me of its enthralling premise. A premise that forces me to ignore the clock for just one more turn. You have a bad run, so you want to go again. You have a good run—so you want to go again. Developer Four Quarters nailed it, and publisher Devolver Digital knew it.

Loop Hero is confident in its own vague and obscure nature. It lets you feel smart just from figuring out the optimal placement of a meadow in order to make it a blooming meadow. You get aha moments over and over again, as you learn what happens to a vampire when you drop it next to a town versus dropping it in a swamp. You build your deck with cards that race you around the loop in order to beat the sunrise, or take your time so that your regenerative powers kick in more over time. And even though battles play out in a real-time setting that you don’t directly control, you feel in control more than ever when you min/max your gears’ abilities to turn you into a tank, or into an area-of-effect monster, or into a slippery evasive nightmare.

That’s where Loop Hero will fool you. It looks like an idle game that you can partially ignore with Netflix running in a second window. It looks like a cookie clicker where just tapping on the screen will win fights and auto-level you up to the next thing. Loop Hero couldn’t be further from that. It will take your time, yet instill you with energy, and it will suck up all your focus, yet spit out only the amount of density you’re looking for. And if the gameplay wasn’t already good enough, the knife’s edge that cuts through the writing is continuously surprising in its wit, anger, love, and treatment of memory. And stop me if I end this review before mentioning the absolute brilliance of the retro-stylings in the lonely, deviant, sucker punch of a soundtrack. Loop Hero ties it all together.

Rating: 9 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile